The dissertation has arrived, and it’s a scary thing. You might actually be some way into it before you realize it’s a scary thing, or it might be some way off yet and you know already that it will be a scary thing. In either case, it’s tempting feel as though you’ll figure it out as you go or that your coursework will have adequately prepared you for what is to come.

Actually, coursework at many universities works to orient candidates to the dissertation—you might plan studies in your qualitative and quantitative research courses, and you might even go so far as to find a literature gap in a research-focused or other class. No matter how comprehensive the program and how rigorous the courses, it really is that you learn it all as you go through the dissertation.

That said, it’s definitely possible to plan ahead and know what is to come and what to watch out for. When candidates reach out for help with the dissertation, it’s often that they’ve hit one or more roadblocks. They might be stuck, and they might actually need to redo some of their work as they put it in reverse to then try a different road.

Here, we’ll talk about 10 of those biggest mistakes that can derail a study. While they’re grouped roughly by stage, it’s really important to consider all of them up front, even when you’re planning out your study.

Just like getting into a pool or large body of water, it’s not possible to do gradually or without goggles. And here we go!

Topic Development

We have a whole video about this on another part of our site, but providing dissertation coaching at the start like this is also really important—again, there’s so much to think about and things move really fast! So much can go wrong when you build a foundation for a house at speed.

-

Not finding a research gap. This can look like a bunch of things, all of them wrong. The start of the research process is so fun! It’s exciting, and you’re finding so much information that offer help, you know, for that one part of your dissertation, in that one chapter, with the information and the data. In short, you’re not sure, but you just keep researching. For this to work out well, the goal shouldn’t be finding 500 sources; it should actually be finding three. Indeed, the study you conduct must be driven by a gap in the literature—something that is not currently known but that, because of the study you’ll eventually conduct, will be known. Finding all those sources can definitely feel comforting, like they provide a bulwark against hard times, but they can also be a burden. Instead of thinking about how many, think about what: As you read a source, it’s important to review what conclusions it reaches and what questions it leaves unanswered—these are often found in the limitations and recommendations sections. These should lead you to try and find these answers. When you start to find sources that are circling like vultures around a poor, vulnerable research gap, then you know what you’ll need to address. The alternative: You have what you think is a gap, but then you write your literature review. After writing all 40 pages, you realize that your study has already been done. Save yourself!

-

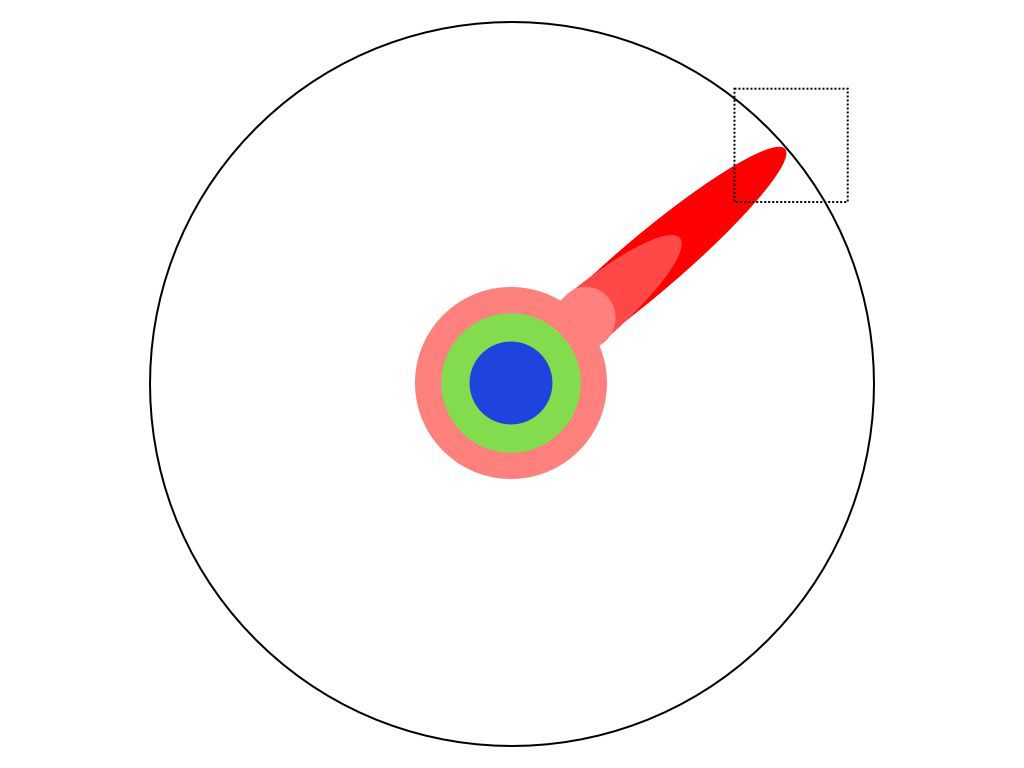

Change-the-World Syndrome. The dissertation is a Big Thing. If it was ever printed—I really hope no one prints those things, or any things, anymore—it would take up a bunch of space. This creates the feeling on the part of many candidates that, to make something taking up that much space, the dissertation will need to be all. In our dissertation consulting work, we sometimes see purpose statements, in particular, that have so many parts, all moving in slightly different directions. Instead, the dissertation should really be just about one thing: one phenomenon, or one set of relationships. It creates a tiny bit of new knowledge, like this:

That little contact point at the edge of the circle is tiny! That’s the portion you’re aiming when you take on doctoral research, and “arc” is not an appropriate word for its scope!

The Research Process

Once the topic is selected, the real fun begins! Or continues, maybe—the research done to define a research gap and being the foundation of the study does go on and in the much longer form of the literature review. Because it’s so long—often the longest chapter in the dissertation—it’s critical to get it right.

-

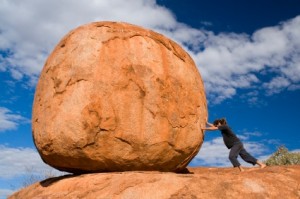

Literature review procrastination. Once you do find a specific gap and you make your study about pushing on that little spot to create new knowledge, you’ll have to formulate the research basis for your study, articulating the need for the work you’re taking on. Part of that is done in the problem statement, yes, but it’s done in longer, much more tedious form in the literature review. For many universities, the requirements are daunting: 40 pages and at least 75 sources with at least 85% published in the last five years. It’s easy to focus on the introduction and methodology that can often be done at the same time, partly because for many candidates, the literature review is the longest single research work they will have ever written. When we provide assistance at this stage of the dissertation, we help clients see the literature review as not one big boulder-up-a-hill trial, but rather a bunch of little ones. Thankfully, while they’re still boulders, they’re much easier to push, and breaking up the literature review into little parts like that can make the whole thing much easier.

-

“A Disturbing Lack of Vision.” No one wants to be describe this way—yikes! It’s also nice if things associated with you, like the literature review, are also not described this way. One common problem we find in consulting is with dissertation literature reviews that are devoid of the vision of the study and what it will achieve—rather than making cogent arguments in favor of the focuses and methodological approaches of those studies, they instead amount to really well-organized annotated bibliographies, spending one paragraph on each source. Literature reviews like these often get locked in revision for ages, as candidates do everything they can to avoid rewriting all 40 pages, eventually succumbing to that terrifying need. To avoid this fate, put your literature review topics in order such that they narrow progressively toward the research gap, which should come at the end of your literature review. Then at paragraph level, start each with a strong, ideas-focused claim—your claim—that you then use two or more sources to prove. Remember, too, that some of these claims will need to be about what questions are left open or created by the literature, particularly as you get closer to your research gap. There has to be some uncertainty for your study to resolve!

Talking to People, Number-crunching—That Sort of Thing

This last set of pitfalls concerns the methodology and analysis. They’re the meat and potatoes of your study—while delicious, it’s totally easy to mess them up! In terms of chapters, these don’t arrive until chapters 3 and 4 of the dissertation. However, it’s best to be thinking about them right away! Again, going in reverse is particularly unpleasant when it comes to the dissertation.

- Variable and survey snafu. This can happen easily, and it’s actually one of the downsides to a quantitative study—your chosen variables must line up perfectly with the data that are found or collected. While there are roughly a gagillion (a technical term) survey instruments out there, often with many devoted to measuring the same variables, you might find your efforts stymied by the lack an instrument that measures the variables in your study. Perhaps it does, but not in the ways that you define them or your study. All of these present challenges that need to be worked through. You might think, “I can just design my own instrument!” And you can! I should mention, though, that this is a significant undertaking, one that comes with it a number of obstacles. The main one is a pilot test, which involves a separate round of data collection and then testing to determine some of the psychometric properties of your instrument—always internal consistency reliability, and perhaps construct validity. This testing is not easy. Indeed, for these reasons, some programs do not all candidates to attempt instrument development, requiring instead that candidates use only a pre-validated one (or more) to measure their variables.

- No plans for coding. Candidates might think they’re side-stepping the difficulties above by doing qualitative research—I mean, they’re words, right? How could they be difficult? I’m using words even right now to talk about it! This is quite true, but the work of qualitative analysis can even be harder than is statistical analysis, as there is no program in which you can click some buttons and the analysis be done for you. There are programs like NVivo for qualitative analysis (it’s our preferred program–it’s like SPSS for statistical analysis), but even this is just like Word for your dissertation—it makes the process cleaner and easier than doing by hand. That’s it. It means you have to have a plan, and going through the methodology development by saying, “I’ll examine the transcripts to find themes” does not work! Instead, coding is necessarily a multistep process, usually inductive, and with at least two discrete rounds of analysis—including at least one that requires that you make no inferences at all. The methods chapter will likely need that multi step plan to be described to meet with approval. Even if it doesn’t, you’ll definitely need that plan when you do the analysis.

- IRB blues. All of the above is moot if you can’t access a group of participants from which to collect data (if you’re collecting primary data). In providing dissertation help to clients, we find often that, irrespective of the pre-IRB stage they’re in, they’re working with a plan to sample from a population they won’t be able to. Indeed, we’ve seen candidates be rejected after they get to IRB, stopped from sampling from a vulnerable population—perhaps children under the age of 18, the elderly or infirm, those currently incarcerated, or even people the researcher knows outside of their capacity as researcher. Then they have to go back to the drawing board. It’s possible in some instances to change the population and sample slightly, maybe sampling from a group of professionals who work with the vulnerable population, but in many cases, this doesn’t work for a dissertation. Timely coaching can help to solve the problem before you get too far.

- Early bird gets the worm, or maybe can’t find one. Another mistake we see many candidates make is to not know about IRB in the first place or perhaps to disregard it, collecting data long before they should or, in ethical terms, are able to do that collection. IRB is what allows candidates to even start recruiting; before that, no potential participants can even be contacted, and the most that can be done is to get organizational partners in place to help with that recruitment. I’m actually going to throw in one more problem here—why not! I make the rules—and talk about an even bigger one: Just assuming you’ll be able to access the participants you need. It might not actually be that small business owners victimized by identity theft will agree to be interviewed or surveyed, and teachers at a school a person used to work at might not be willing to talk with someone they know already about sensitive topics. This is a problem more often when the researcher doesn’t know the group of people in advance, but it can be an issue either way. Being realistic about the ability to get the data you need can help to avoid this problem. Talking with someone who can help with the dissertation and developing methodology is also useful—they can guide you through what to expect, as they’ve definitely encountered any issues you’re grappling with before.

- Developing a line when you need a triangle. For qualitative research, particularly case studies, it’s necessary to achieve something called triangulation. It’s the qualitative equivalent of validity, and it is necessary to ensure that you’re able to understand the phenomenon fully and realistically. It means collecting three or more types of data (so when you connect the data points, it’s a triangle you get!) and then analyzing them together to bring them in conversation, using each source to provide a “check” of sorts on each other source. Let’s say again that you’re studying an anti-bullying program’s roll out in an urban district. You’ll definitely want to interview the “boots on the ground”—those teachers responsible perhaps for developing curriculum but at least in charge of delivering those lessons through sound methods and in ways that allow children to learn. However, teachers are good at having opinions, and insofar as they are people, they have biases (so do, by the way, any administrators or parents or students who are also interviewed—they’re people too!). Encountering a group of educators who feel as though the new principal is cold and unsupportive would result in a bunch of interviews that convey that. They might be right-on, actually, but in any case, you’re not getting from them a sense of the phenomenon; you’re getting a sense of their perceptions of the phenomenon. Since these two things are not the same, supplementing with at least two other sources is a great idea. The “classic” case study in education involves both observations (perhaps the curriculum in action or planning meetings) and the analysis of documents (communication with parents or curriculum materials). However, other options abound, and focus groups and questionnaires are but two of them. One final note: Please see the I’ve not mentioned the memos or notes jotted during interviews as a data source. Sometimes these are called field notes, but they’re actually just part of the interview data source. A researcher journal can also be a powerful way to help ensure integrity in your findings. Again, though, it’s not a source of data. There’s no way getting around this need, and as you take on your qualitative analysis, you’ll want those three legitimate data sources!

- Confirmation bias. As I alluded to above in talking about teachers and others wrapped up in that intervention: Everyone who is a person has bias. Including the researcher. Actually, for qualitative studies, there is most often a section called Role of the Researcher or something like that (section names vary), but the goal here is in part to describe any of those biases, even expectations about what the results of the study will be. It’s perhaps the biggest mistake of all to presume that you don’t have any expectations or biases.

If you’ve ever done one of these, then personhood has been conferred upon you, and you have biases. It’s expected that you’ll talk about them in that section, and keeping the researcher journal that I described above can be a really powerful way to control for those. I’m sorry to break this to you, but that scary game Ouija works because people have expectations of what the answer to a question will be and subconsciously steer the device (lens? widget? Inspection glass?) in the direction of the letters that spell out that answer! People are moving their own hands! And they don’t realize it, swearing instead it’s the game. Imagine how this works for your study—without being aware of and controlling for what you want the results to be or even just what you think they will be, you’re liable to ask leading questions and then analyze data in ways that confirm your thinking. On a related note: It’s necessary to have good interviews with insightful questions connected directly to your aims. Interviews are hard, but if they result in yes or no answers, a lack of follow-ups, generally insufficient responses, then the work of qualitative analysis becomes very difficult, indeed. In the dissertation help we provide, we find this is most common when questionnaires are used in place of interviews, so it’s a good idea to avoid this to the degree possible.

The More You Know

The aim here has not been to overwhelm, though you might be feeling a bit anxious! That’s to be expected, and it might continue as you feel you know these and then find that they’re something else altogether when you (attempt to) apply them to your dissertation. The decisions are not easy ones, but because they are so important, it’s a good idea to get someone to help. Even bouncing ideas for your dissertation off a consultant who can give food for thought and a tentative direction is worthwhile—it can save such heartache. And tuition!

Relying on someone who knows in this way just makes sense, no matter what stage of the process you might be in. Your coursework was beneficial, to be sure, but with these additional understandings and the ability to avoid the various pitfalls in the process, you can get to graduation a lot easier!