Studies that use qualitative research and analysis often make use of interviews as the primary, if not sole, source of data. Qualitative interviews can be quite structured and fact-based, but in most forms of qualitative research, especially in thesis or dissertation research, qualitative interviewing takes the form of a “guided conversation” rather than a job interview-esque procession through a series of targeted questions (see Warren, 2002).

If you’re completing qualitative research and analysis for your dissertation or thesis, it’s far more likely that you’re aiming to conduct your interviews “to derive interpretations, not facts or laws, from respondent talk” (Warren, 2002, p. 83).

Interview Structure

In the process of dissertation or thesis writing, the structure of your interview is established in the proposal. So, you need to stick to the planned structure for different reasons. One big reason for this is that you’ve written up a rationale for use of a structured, semi-structured, or unstructured interview format in your IRB application, which included submission of the actual interview instrument as an attachment.

Given that the IRB application is your gateway to ethical approval to collect data from your participants, what do you imagine might happen if your actual interview procedures strays from what was approved by the IRB? Well, at best you might be required to modify your research protocol, but at worst, the approval to continue with your study might be revoked completely. Not pretty, agreed.

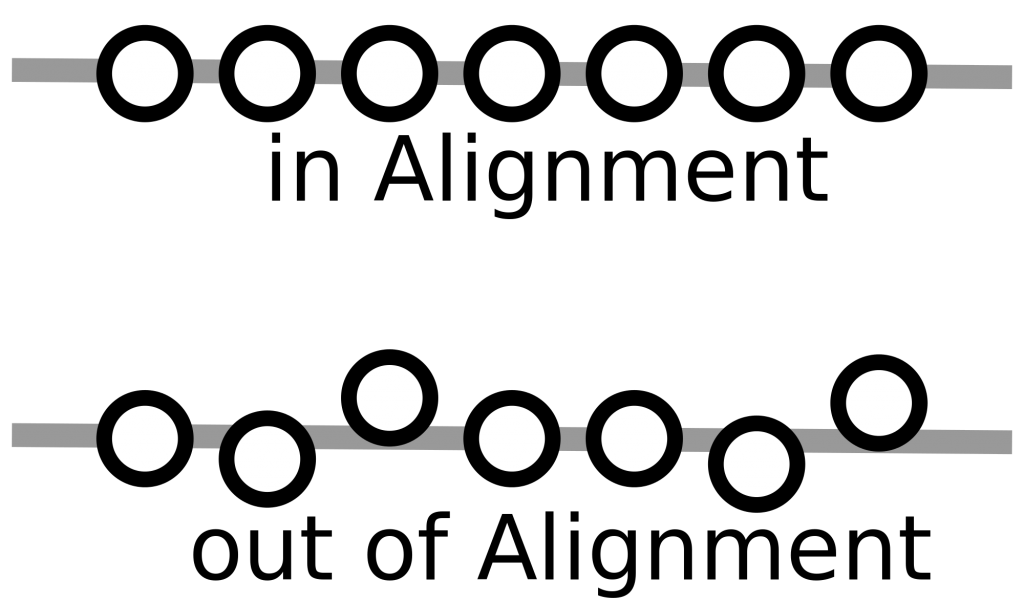

Although straying from your interview structure as initially planned can have ethical implications for your participants the IRB is concerned with (i.e., if you delve into an unstructured exploration of sensitive topics that weren’t approved by the IRB), there is also the major concern related to research integrity. If you’ve gotten very far into your dissertation or thesis, writing up your methods is clearly all about alignment. I’m sure you’re well-acquainted with the concept of alignment by now, and this remains vital to the integrity of your study all the way through data collection and completion of your qualitative analysis.

If you’ve set up a semi-structured interview approach to align perfectly with the phenomenon of interest, but then you prompt your participants to go off on unstructured tangents that do not fully cover all aspects of the phenomenon of interest, you’ll be needing some serious help with your dissertation or thesis when you end up with data that might be very interesting, but that do not fully answer your research questions.

We’ll discuss examples in a bit, but first let’s look at the three major types of interviews for qualitative research, which are (a) structured interviews, (b) semi-structured interviews, and (c) unstructured interviews.

Structured interviews. This type of interview is appropriate when it is important to obtain specific types of information on a set collection of questions.

The interview is structured because the researcher follows a specific set of questions in a predetermined order with a limited number of response categories. This would be appropriate to use when interviews require that the participant give a response to each ordered question, which are often shorter in nature. (Stuckey, 2015, p. 57)

Although open-ended items might be included, this is not an especially exploratory form of interviewing for qualitative research. Because of this, it is used when the researcher already knows quite a bit about the topic at hand but needs additional data from a large number of participants to flesh out knowledge on the topic.

For example, let’s say that you want use your dissertation to help online daters to have better first dates. You’ve scoured the research on strategies for making a great impression during the first date with a person met through online dating websites. With the multitude of quantitative and qualitative research out there, you’ve been able to gather together a handful of commonly reported strategies. But you want to use your dissertation to specifically help online dates in your own region (no particular reason for this, just your unselfish benevolence toward others). And you want to gain a sense of how these (and maybe other) strategies are used in your particular region, and why.

So a closed-choice survey isn’t really going to work, because you want to allow for new strategies to emerge and also because you want to gain a sense of why people prefer certain strategies. You could definitely learn a lot about this through conducting in-depth interviews with people, but as you’re really looking to glean this information from a large sample of online daters, conducting super long interviews really isn’t a great idea. The structured interview is a sort of middle ground that technically falls within the qualitative research paradigm, and it might look something like this:

Question 1. From the following options, which strategy do you typically use to make a good impression during your first date with a person you’ve met through an online dating website, and why?

a. Talk about how cool and funny you are

b. Show your date pictures of all your ex-girlfriends

c. Buy the most expensive wine on the menu and wax poetic about its “bouquet”

d. Insult the waiter’s shoes

e. Get really really drunk

f. Other_________

I know, I know…you’re probably thinking what I am: “Do I have to pick just one? They’re all so effective, especially when you do them all at once!” And, this is why some of us are still single, but that’s not of central concern here (or, it might be, given your problem statement).

The point is that you can keep the information conveyed in the interview pretty tightly controlled while still allowing for a bit of flexibility in the responses. This flexibility that stems from the open-ended question, “Why?” is what brings in the variety of responses qualitative research is known for.

Much more likely, though, is that you’re using qualitative research and analysis because you want to explore the variability of perspectives and experiences to a much greater degree. Dissertation or thesis writing is often driven by a passion for an area of research where little is known, and a desire to help move knowledge forward in this area leads to you much more in-depth and detailed inquiry. This is where the semi-structured and unstructured interviews come into play, and we’ll discuss these next.

Semi-structured interviews. The semi-structured interview is just what it sounds like, and has an underlying structure created by your core questions while also allowing the option to explore new avenues of thought with your participants as these opportunities arise. Let’s consider the following:

The semi-structured interview involves prepared questioning guided by identified themes in a consistent and systematic manner interposed with probes designed to elicit more elaborate responses. Thus, the focus is on the interview guide incorporating a series of broad themes to be covered during the interview to help direct the conversation toward the topics and issues about which the interviewers want to learn. (Qu & Dumay, 2011, p. 246)

Thesis and dissertation projects that utilize qualitative research and analysis most commonly involve use of the semi-structured interview with probe questions. We’ll talk more specifically about how to set up probe questions or prompts a bit later, but their function is to draw out more detailed and complex responses from your participants in cases where they (a) respond very briefly to your main question, or (b) touch upon a perception or idea in the course of responding in full to your main question, and you think that exploring that idea or perception in more detail will contribute meaningfully to your dataset and resulting qualitative analysis.

To ground this in an example, let’s say that you’ve finished your qualitative analysis of the structured investigation of online daters’ first-date strategies for making a good impression. You think that it would really help those unnamed online daters in your specific region if you build upon your dissertation research to a greater degree.

Imagine that you discovered that “Get really really drunk” was the dating strategy most frequently reported by participants in your study, and you’re wanting to dig a little deeper to learn about the lived experiences of your online daters with regard to this choice. Surely it’s a choice that comes with costs, and it’s hard at first glance to see what, if any, benefits this strategy might confer. You arrive at a collection of key themes from your literature review that might be worthwhile to explore, but you also want the freedom to delve into your participants’ realities to learn how they make sense of this dating strategy based on their lived experiences. (If you’re thinking this sounds like phenomenology, you’re right!)

Question 1. Why is getting really really drunk your preferred strategy for making a good impression during your first date with someone you met through an online dating website?

Possible probe question: Tell me more about that date.

Possible probe question: Can you describe the end of the date a bit more?

Possible probe question: Tell me about your date’s reaction to that.

I’m sure you can imagine how such an interview might progress, and also how the level of detail would be much greater in comparison with the structured interview approach. This level of detail is one of the big strengths of qualitative research and analysis. Instead of the short answers you’d obtain using the open-ended structured interview approach you used in your dissertation, in a semi-structured interview like this one, you would hear longer stories that help to clarify your participants’ perceptions, thoughts, interpretations, explanations, etc., which provides very rich data for qualitative analysis of various sorts. This level of detail in participants’ accounts also allows you to provide “thick description” in support of your themes, or direct participant quotes that illustrate each theme.

Unstructured interviews. The third major type of interview for qualitative research is the unstructured interview. Let’s consider the following:

The unstructured interview proceeds from the assumption that the interviewers do not know in advance all the necessary questions. From a romanticist point of view, interviewers are empathetic listeners exploring the inner life world of the interviewees, acknowledging that not all interviewees will necessarily understand questions worded in the same way…Therefore, in an unstructured interview, the interviewer must develop, adapt and generate follow-up questions reflecting the central purpose of the research. (Qu & Dumay, 2011, p. 245)

This type of interview structure is great for qualitative research that aims to understand participants’ narratives or life stories, as they understand and make sense of them. In thesis or dissertation projects that use narrative analysis or ethnography, the unstructured interview is just perfect. The comparatively loose structure of the interview does help to generate data that are relevant to one’s topic of concern, but that emerge from the participant’s own particular ways of thinking and talking about the topic of interest.

Next, let’s go over some specific Do’s and Don’t’s regarding interview structure:

| Interview Structure | |

|---|---|

| DO’s | DON’T’s |

| Follow the interview guide | Make up new questions as you go along |

| Stay consistent with the interview structure (i.e., don’t take an unstructured approach when your methods specify semi-structured) | Use probe questions in a structured interview |

| Skip ahead to future questions in the interview guide if the participant’s response to an earlier question leads naturally to this future question | Stick rigidly to the sequence of the interview questions on your protocol if a more natural sequence arises during the interview |

| Come back to any skipped questions to make sure you hit them all in your interview | Skip questions from the interview protocol entirely during the interview (unless this is the participant’s choice, in the case of extreme psychological distress, for example) |

Open-Ended vs. Closed-Ended Questions

Another area that’s super important to think about when planning an interview for a qualitative research project is the phrasing of your interview questions. When conducting qualitative research and analysis, using open-ended questions is very important. Why is this?

A closed-ended question can only result in one of two answers—yes or no. These types of questions will not allow the interviewee to offer you any additional information. The goal of qualitative research is to uncover as much about the participants and their situations as possible and yes or no questions stop the interviewee before getting to the “good stuff.” (Jacob & Furgerson, 2012, p. 3)

We definitely want you to get to the good stuff in your interviews, because this is what qualitative research and analysis are all about; so, let’s go over the difference between open-ended and close-choice questions. A closed-ended question is one that can have just yes/no responses as Jacob and Furgerson (2012) pointed out, but in qualitative research interviews you’ll also want to avoid those questions that elicit short, categorical responses as well.

For example, you might ask the question, “Where did you go for your most recent first date with a person you met through an online dating website?” You can see that this question is not a yes/no question, but it also won’t necessarily result in a lengthy and detailed response.

Participants might respond with answers like, “To dinner and a movie,” or, “To the dogtrack.” Yes, there are some chatty Kathy’s out there who will tell you their life stories if you merely happen to look in their directions, and from those types of participants, even this poorly worded might elicit responses like, “Where’d we go on the first date? To Goofy’s Grill, because they have a full bar with EVERY liquor imaginable, and they don’t cut you off like other places, you know, like if you fall asleep on the table or something. But there was this one time…” Oh, don’t date that guy.

An open-ended question that might be a better choice for qualitative research could be something like, “How did you decide where to go on your first date?” The open-ended question doesn’t even have to be a question, truly. It can be a statement that encourages your participants to open up. Consider this:

The phrase “tell me about” is not only an invitation for the interviewee to tell you a story, but also it assumes that the interviewee will talk and it subtlety commands the interviewee to begin talking. Also the phrase “tell me about” makes it almost impossible to create a question that is too complicated, too detailed, or too difficult to answer. (Jacob & Furgerson, 2012, p. 4)

| Open-Ended vs. Closed-Ended Questions/Items | |

|---|---|

| DO’s: Examples of Open-Ended | DON’T’s: Examples of Closed-Ended |

| How did you learn to play the triangle? | Which techniques did you use to learn to play the triangle? |

| Tell me about the ugliest outfit you’ve ever worn. | What color is your ugliest outfit? |

| Share a story about your first day of kindergarten. | Did you have to be dragged to the door on your first day of kindergarten? |

| Why did you choose to study insect psychology? | Do you feel a sense of kinship with bugs? |

The Role of the Researcher

If you’re using qualitative research and analysis for your dissertation or thesis, you’ll likely be called upon to discuss the role of the researcher in your methods chapter. In qualitative research, the researcher is considered an instrument of data collection, and as you work so closely with the data as it’s being collected and analyzed, can help to understand how your personal relationship to the topic comes into play.

Among other things, this means recognizing any biases that might influence the ways that you interact with the participant during the interview. You might have certain expectations or beliefs that you convey in subtle or not-so-subtle ways. Another consideration related to your role in qualitative research interviews is that you’re responsible for protecting the participant from harm, but as a researcher (and not a friend or counselor), it’s inappropriate for you to console or offer advice to participants, even though you might really want to do so. Here are some Do’s and Don’t’s regarding your role as the researcher as this comes into play during qualitative research interviews:

| The Role of the Researcher | |

|---|---|

| DO’s | DON’T’s |

| Ask neutral questions that avoid expressing an opinion or desired response (i.e., “How would you describe your interactions with men in the workplace?”) | Ask leading questions (i.e., “Why do men always ignore women in meetings at work?”) |

| Respond to what participants are telling you in a neutral manner | Express agreement, disagreement, approval, or disapproval of what participants share in interviews |

| Use a neutral, reflective listening type approach to acknowledge emotions participants express (i.e., “That must have been hard for you,” or “It sounds as though you were very happy about that”) | Respond in an attempt to soothe, comfort, or counsel the participant, as this is outside of your role |

| Offer to take a break or discontinue the interview, or to move forward to next question if the participant is showing clear psychological distress | Ignore signs of psychological distress when participants show these |

Probe Questions

We’ve touched upon the function of probe questions or prompts for eliciting rich data to support your qualitative analysis, and these probes create the “semi” part of the semi-structured interview so often used in qualitative research and analysis. Learning how to use probe questions effectively is a huge help in drawing out sufficient data for your dissertation or thesis analysis. So, let’s look at these in a bit more detail:

Prompts also help to remind you of your questions while at the same time allowing for unexpected data to emerge. To use prompts effectively, you must first design a broad question (as mentioned in tip # 8) that might take an interviewee in several different directions. Directly under this question, you should design bullet points that remind you of areas that have emerged from the literature or things you think will enrich your data. (Jacob & Furgerson, 2012, pp. 4-5)

Here are some Do’s and Don’t’s regarding probe questions as part of semi-structured interviews:

| Probe Questions | |

|---|---|

| DO’s | DON’T’s |

| Encourage participants to share more detail about interesting and topic-relevant information they bring up | Go way off topic |

| Use orienting cues and neutral prompts to encourage topic-specific elaboration (i.e., “You mentioned feeling a connection with June bugs; say more about that”) | Use probe questions to challenge or question the validity or accuracy of what a participant shares during the interview |

Nonverbal Communication

Finally, nonverbal communication is another big consideration when conducting interviews for qualitative research. Think about this:

It is worth your time to read a basic book on counseling techniques so that you may learn how to become a good listener with whom people feel comfortable sharing their stories. Learning skills such as attending and reflection (Conte, 2009) coupled with understanding nonverbal behavior help people understand that you are not only listening, but you are also understanding what they say. When people feel heard and understood, they are more likely to share. (Jacob & Furegerson, 2012, p. 8)

Here are some Do’s and Don’t’s regarding nonverbal communication during interviews for qualitative research:

| Nonverbal Communication | |

|---|---|

| DO’s: Examples of Open-Ended | DON’T’s: Examples of Closed-Ended |

| Make eye contact to confirm that you are listening | Stare the participant in the eye without looking away for long periods (this is weird) |

| Nod to communicate “I hear you” in a neutral manner | Nod or shake your head in ways that communicate agreement or disagreement |

| Maintain an open posture facing the participant | Present a closed posture (i.e., arms crossed, body/face turned away from the participant) |

| Take intermittent notes on key points or thoughts that might aid analysis later, only after explaining that this is what you intend to do | Hug or touch the participant, except for a handshake if the participants seems OK with this |

That’s a broad overview of techniques and considerations that should help greatly in your dissertation or thesis writing if you’re planning a study that uses qualitative analysis. It’s amazing that something so intuitive as a conversation can be so complex to set up as a process of data collection to support qualitative research and analysis in your thesis or dissertation, and given this complexity, it’s always OK to seek dissertation help if you need it!

References

- Jacob, S. A., & Furgerson, S. P. (2012). Writing interview protocols and conducting interviews: Tips for students new to the field of qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 17(42), 1-10. Retrieved from http://nsuworks.nova.edu

- Qu, S. Q., & Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 8(3), 238-264. doi:10.1108/11766091111162070

- Stuckey, H. L. (2013). Three types of interviews: Qualitative research methods in social health. Journal of Social Health and Diabetes, 1(2), 56-59. doi:10.4103/2321-0656.115294

- Warren, C. A. (2002). Qualitative interviewing. In J. F. Gubrium & J. A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research: Context and method (pp. 83-102). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.