As you develop your dissertation topic and research plan, you are faced with many choices that will ultimately affect how your study is focused and what types of questions you can answer through your analysis. Major decisions regarding your method, design, population, and data collection process require that you understand the differences between your options. Understanding such differences on key decision points will help you to configure your study optimally so that you are addressing the core questions that motivate you to conduct this research.

Being prepared to speak concisely about the differences between various components of your research plan will also help during your proposal or final dissertation defense. When explaining your choices (i.e., of quantitative versus qualitative research method, or your specific qualitative analysis protocol), it is important to explain not just why you made the choices you did but also why you didn’t choose your other alternatives. There are also key terms that new researchers tend to mix up (i.e., sample and population), and using these terms correctly in your manuscript and defense presentations will certainly reassure your committee that you grasp the fundamentals of the research process. So, let’s start out with one of these common points of confusion, method versus design. (And if you missed our first blog post outlining some of the key concepts for dissertation or thesis writing, you can find that here.)

Method Versus Design

One of the most important distinctions you’ll need to understand is that of research method versus research design, and it can be a difficult distinction to grasp because both the method and design revolve around the types of questions you develop and the various ways you construct your study’s procedures so that they effectively address these underlying questions. A helpful way of thinking about the distinction is to keep in mind that the method is broader than the design and that there are only three methods: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods. Within each of these methods, there are various designs that you can choose that align with your much more specific focus or aims.

For example, if you wanted to conduct an exploratory study of veterans’ experiences of returning to family life following overseas combat, you would choose a qualitative research method due to its usefulness in exploratory research. Then, the research design you choose would need to align with the more specific application of this exploratory method. If you wanted to hear veterans’ extended stories, narrative analysis would be a suitable research design. If, however, you wanted to explore a collection of specific aspects of veterans’ lived experiences with an emphasis on their interpretations of these experiences, phenomenology would be a better fit. To recap:

| Research Method | Research Design |

|---|---|

| General approach to the study, aligning with the types of questions you want to ask and how to best answer these | Particular application of the method, based on specific focus and aims of the study |

| Quantitative research method | e.g., correlational, causal comparative, experimental |

| Qualitative research method | e.g., phenomenology, case study, narrative analysis, ethnography |

| Mixed Methods | e.g., sequential, concurrent |

Quantitative Versus Qualitative

Many of the terms to follow emerge from the specific research method they align with in your dissertation, and so it will help to preface this with a brief discussion of the difference between quantitative and qualitative research methods. Studies using a quantitative method are those that are aimed at determining differences or relationships between variables that can be counted (Bernard, 2013). It is important that variables be quantifiable because quantitative studies use statistical analysis to obtain results that answer the research questions.

Conversely, a qualitative research method is better suited to open-ended exploration of topics where research questions are best answered using language-based data (i.e., interviews, written documents; Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). You might choose an exploratory approach when your topic has not been thoroughly studied and no instruments exist that would permit a quantitative investigation. Or, there might be existing instruments and plenty of quantitative research on the topic, but if you want to explore how people think about or interpret that topic, then you will need the more in-depth discussion that qualitative analysis can provide. Mixed methods studies are exactly what they sound like: a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methods in a single study. To recap:

| Quantitative Research Method | Qualitative research Method |

|---|---|

| Focus on relationships or differences | Focus on exploration, increasing understanding |

| Predefined, quantifiable variables | Phenomena of interest, not variables |

| Numerical data | Language-based data |

| Statistical analysis to address RQs | Content or thematic analysis |

Variables Versus Phenomena of Interest

We touched on the uses of variables versus phenomena of interest in the previous section, and you probably noticed that variables are of interest in quantitative studies and phenomena are focused on in qualitative studies. Variables and phenomena of interest can be associated with the same focal topics, but there are key differences that permit their alignment with specific methods. To align with a quantitative method, variables must be numerically measurable; this permits statistical analysis. For example, use of the Ethical Leadership Scale and the Organizational Trust Inventory to measure ethical leadership and organizational trust, respectively, would allow for a statistical analysis to determine if these variables are correlated.

Just because ethical leadership and organizational trust can be used as variables in a quantitative study, however, that does not prevent you from casting these as phenomena of interest in a qualitative research study (in case you’re wondering, phenomenon is just a fancy way of saying “a thing that happened”). If you were less interested in the correlation between these variables and more concerned with how workers perceive the influence of ethical leadership on their perceived organizational trust, then a qualitative exploration would be better aligned with your focus. Instead of presenting leadership and trust in terms of operationalized variables, however, you would instead present them as your phenomena of interest (i.e., workers’ perceptions of the influence of ethical leadership on perceived organizational trust). To recap:

| Variables | Phenomena of Interest |

|---|---|

| Predefined/operationalized, know exactly what you are measuring before data collection | Defined but with room for exploration and elaboration through qualitative analysis |

| Quantifiable, can be counted or measured numerically | Not quantified, often involving perspectives, perceptions, descriptions, interpretations, stories |

| Instruments require validation | Instruments do not require validation but expert panel review is good practice |

| Instruments must be closed-choice to generate numerical results | Instruments must be open-ended to elicit rich, detailed perspectives |

Explore Versus Examine (or Purpose Statement Verbs for Quant vs Qual)

As the previous section illustrated, establishing alignment in your dissertation is often about making nuanced choices (i.e., differentiating between variables and phenomena of interest)—and probably the main reason doctoral candidates reach out to us for dissertation assistance. Emerging researchers in the dissertation editing process are often surprised to find that simply picking the incorrect verb for the purpose statement can create misalignment, but alas, this is true. In fact, the purpose statement is one of the most finely-tuned sentences in the whole dissertation, as you need to state your purpose both concisely and thoroughly. Choosing the perfect wording for a purpose statement is one of those annoying examples of “it’s easy when you know how,” which is no less frustrating to hear when you don’t know how. So, it will help to go over the basics.

Of course, for studies using both quantitative and qualitative research methods, you’ll need to state the method, design, variable/phenomena of interest, and the target population in your purpose statement. These are the constants in purpose statements across all methods and designs, but what changes in alignment with specific method and design combinations are the key verbs. These key verbs link back to the basic analytic function of your study, and as these functions differ based on your method and design, so too must the key verbs differ. With qualitative research and analysis, by far the most commonly used verb is “explore,” which aligns with the fundamentally open-ended and exploratory nature of qualitative research. An example follows:

The purpose of this qualitative single case study is to explore instructor and student perspectives on strategies for increasing student engagement in fully online undergraduate courses at a large public university system in the western United States.

From this example, you can see how the key verb “explore” is connected with the phenomenon of interest, “instructor and student perspectives” on the topic, which aligns with the qualitative research method. A very common rookie mistake is to use verbs that are aligned with a quantitative method, such as “examine,” “investigate,” or “determine,” in a qualitative dissertation purpose statement (or vice versa). But, in keeping with the exploratory nature and focus on phenomena of interest, qualitative research purpose statements should only use verbs that reflect this capacity of the method. Qualitative research and analysis can also help develop understanding of phenomena, cultivate understanding or insights, etc.; however, only quantitative studies can examine relationships between variables, as statistical analysis is necessary for such examination. Let’s look at a sample quantitative purpose statement:

The purpose of this quantitative correlational study is to investigate the relationship between instructor engagement and student engagement in fully online undergraduate courses in a large public university system in the western United States.

As you can see, the general topic of this quantitative study is similar to that of the above qualitative study, but instead of stating an intent to explore a phenomenon, this states an intent to investigate the statistical relationship between two variables. Keeping your key verbs and focal points (i.e., variables or phenomena) both aligned with your method and design is essential, as you never want to state a purpose that is actually impossible to accomplish given your chosen method. For example, if you state that the purpose of your qualitative research is to “examine the impact of cable news programming on viewer anxiety,” you’re setting your study up to fail. A qualitative research method would allow you to “explore viewer perceptions of the influence of cable news on their anxiety,” but only a quantitative method would allow you to examine the impact (i.e., via statistical analysis) of one variable upon another. To recap:

| Verbs for Quantitative Methods | Verbs for Qualitative Method |

|---|---|

| Examine | Explore |

| Investigate | Develop understanding |

| Determine | Cultivate insights |

Structured Versus Semistructured/Unstructured Interviews

Studies using qualitative research methods commonly include interviews for data collection, and it is important to understand the types of interview structure and applications of each. Structured interviews include a “specific set of questions in a predetermined order with a limited number of response categories” (Stuckey, 2015, p. 57). The structured interview does not permit much in the way of exploration, and so it is not widely used in in-depth qualitative research. Structured interviews are more useful in studies where the researcher already knows much on the focal topic and needs a large body of largely numerical data to contribute to knowledge on the topic.

In contrast, semi-structured interviews are ideal for gathering rich, in-depth data for exploratory studies while also sticking to an established set of questions. The semi-structured interview follows an underlying structure formed by your key questions while also permitting you the flexibility to explore new avenues of thought with your participants as these opportunities arise. Semi-structured interviews’ open-ended items help to elicit your participants’ perceptions, thoughts, interpretations, and explanations, which provides wonderfully detailed and textured data. The semi-structured format is easily the most widely used in dissertations using qualitative research and analysis.

The unstructured interview can also be quite useful, depending upon your study’s aims. The unstructured approach “proceeds from the assumption that the interviewers do not know in advance all the necessary questions. From a romanticist point of view, interviewers are empathetic listeners exploring the inner life world of the interviewees” (Qu & Dumay, 2011, p. 245). This type of interview structure is ideal for qualitative research that aims to cultivate understanding of participants’ narratives or life stories, as they perceive and interpret them, such as narrative analysis or ethnography. To recap:

| Structured | Semistructured | Unstructured |

|---|---|---|

| Firmly established set of questions | Established set of core questions | Established general topic or focus of interviews |

| No deviation from interview guide | Insert probe or prompt questions as needed between core questions | Allow participants to determine the direction of their responses |

| List of possible responses to each question | Open-ended questions allow for individualized responses | Based on assumption that researcher might not know all pertinent questions |

Sample Versus Population

As mentioned in the introduction to this article, there are certain key terms that new researchers often mix up as they’re learning the ropes of research, and these two are definitely among those. The sample and population both refer to the possible sources of data—usually people—that are of interest in your particular study. The population refers to the full group of people to whom your study topic pertains, and the sample refers to the subset of this broader population that you include as participants in your study. Note, though, that populations can consist of subjects other than people, depending on your field of study. Although people are of interest in human subjects research, populations in other types of research might include subjects like rocks, books, or tree frogs.

Let’s consider an example to help illustrate the difference between population and sample. Imagine that you are conducting a dissertation within industrial-organizational psychology, and you are specifically interested in using statistical analysis to determine the relationship between work-life balance and psychological wellbeing for managers working for a large, globally operational corporation, BigCo. Your population would then include every single manager for BigCo; let’s say this includes 3,500 managers. Clearly this is way more participants than you would want to survey, and so you conduct a power analysis and conclude that 75 participants would suffice. So, you send out 125 surveys to be on the safe side and end up with 81 usable responses. This group of 81 managers is then your sample, which was drawn from the full population of 3,500 managers. To recap:

| Sample | Population |

|---|---|

| Subset of the population | The entire group of people that your study pertains to |

| Representative samples important for quantitative studies | Generalization of results to population important aim of quantitative studies |

| Purposive samples important for qualitative studies | In-depth exploration of specific group’s perspectives or experiences important aim of qualitative studies; generalization is not goal of qualitative research |

Codes Versus Themes

If you’ve chosen to conduct a qualitative study for your dissertation, you have no doubt run into discussion of coding and identification of themes in the data in descriptions of the qualitative analysis process. Qualitative research is often appealing for many doctoral candidates who shy away from statistical analysis, and it is also a very attractive method for those who appreciate the complexity and texture of human experience. But, making sense of the large volume of text-based data requires a systematic approach to ensure a sufficiently rigorous analysis. In their efforts to provide support and dissertation assistance, your committee will want to see that you have a solid command of qualitative analysis procedures both before and after data collection, and demonstrating that you know the difference between codes and themes will help to assure your committee that you know what you’re doing.

Whether you are conducting a basic thematic analysis, a content analysis, or something more ambitious like constant comparative analysis for a grounded theory study, qualitative analysis involves a movement from less interpretive to more interpretive work with the data. Coding is the application of labels to segments of text that reflect the basic meanings contained in that bit of data; the result of coding is a collection of codes, which are minimally interpretive. After coding all of the data, you then move forward to more interpretive work with the data by combining similar codes and asking yourself what they have in common.

Thinking about your collection of grouped codes and how they tie in with your research questions and theoretical framework allows you to develop higher-order themes (or categories, as they are often termed in content analysis). Keep in mind that (a) coding comes first and stays close to surface-level meanings in the data, and (b) grouping similar codes together allows you to identify emergent themes in the data. To recap:

| Codes | Themes |

|---|---|

| Basic units of meaning in text-based data | Higher-order groupings or categories |

| Assigned through line-by-line reading of qualitative data | Developed by grouping similar codes |

| Codes stay very close to the surface-level meanings expressed in the data | Assessing what similarly grouped codes have in common permits identification of emergent themes |

Theoretical Versus Conceptual Framework

The theoretical framework and conceptual framework provide similar functions in a study, which is to create an underlying logic and explanatory structure for your inquiry. There is actually some level of disagreement amongst researchers over the true differences between the theoretical and conceptual framework, and from our perspective as a dissertation consulting firm, we know that this difference of opinion is reflected in the variety of university requirements on this point. Some universities simply require a theoretical framework for all dissertations, but other universities stipulate that a conceptual framework be used for qualitative research studies and a theoretical framework be used for quantitative research studies. If you are completing your dissertation at a university that differentiates between the theoretical and conceptual framework, it will definitely help to understand how these are perceived to differ.

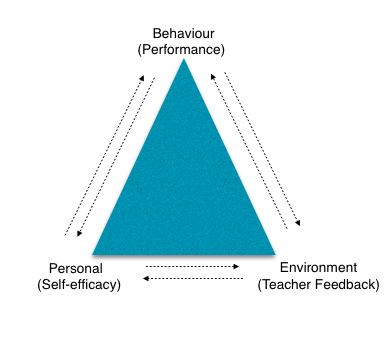

The theoretical framework is derived from an existing theory or a combination of theories, and it needs to align with your topic and research questions so that it will provide a suitable explanatory basis for your findings (Grant & Osanloo, 2014). For example, if you are conducting a quantitative investigation of the relationship between children’s exposure to violence in the home and subsequent aggressive behavior at school, then you might choose Bandura’s social cognitive theory because of its attention to observational learning. On the other hand, if you are conducting a qualitative exploration of youth’s perspectives on their aggressive behavior, you might build a conceptual framework that included processes of observational learning in combination with self-narrative construction and cognitive dissonance reduction strategies.

| Theoretical Framework | Conceptual Framework |

|---|---|

| Used for quantitative and qualitative research studies | Often used for qualitative research studies |

| Derived from existing theory or theories | Proposed network of concepts, processes, and/or variables central to the inquiry |

| Figure might be helpful but usually not required | Figure that visually represents the relationships between concepts, processes, and/or variables of the framework typically required |

Conclusion

Knowing the difference between key elements of your research plan will definitely help you to pick out the optimal pathway for your dissertation research. Whether you choose a quantitative or qualitative research method (or mixed!), understanding differences in key terms is also essential in creating alignment in your research plan. When preparing to defend your choices—whether at proposal or final dissertation stage—it’s vital to review not only the options you selected but also those you did not choose. Being able to speak knowledgeably and concisely (aka, without rambling) will surely impress your committee at defense, and hopefully you found this article helpful in clarifying some of these key differences!

References

- Bernard, H. R. (2013). Social research methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Grant, C., & Osanloo, A. (2014). Understanding, selecting, and integrating a theoretical framework in dissertation research: Creating the blueprint for your “house”. Administrative Issues Journal, 4(2), 12-26. doi:10.5929/2014.4.2.9

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Qu, S. Q., & Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview. Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, 8(3), 238-264. doi:10.1108/11766091111162070

- Stuckey, H. L. (2013). Three types of interviews: Qualitative research methods in social health. Journal of Social Health and Diabetes, 1(2), 56-59. doi:10.4103/2321-0656.115294