Raise your hand if you have at any point caught yourself just typing the topic of your study into Google—like, regular Google—as though it’s going to return anything useful whatsoever? It’s okay, keep them raised. Um, I think it would just be faster to count people who don’t have their hands up.

Heck, my hand is raised. It’s an easy thing to do at midnight when your kids or dog or goldfish are asleep and you’re just desperate to get something, anything, done on your dissertation. If you’re me, though, then the searches get less and less relevant as you go:

- “ESSA replacement NCLB”

- “ESSA and student achievement”

- “Superintendent longevity and student achievement”

- “Average human life span”

- “Who is oldest person ever”

- “How tall am I”

And so on. While these can be enlightening after a fashion, they’re not really great dissertation help. I can say from experience that I’ve learned nothing from these late-night searches (aside from the fact that Jeanne Calment lived to be 122 years and 164 days, a Google-able accomplishment). But databases are so foreign and difficult and burdensome. They’re expensive, for one thing. And in part, it’s because individual articles are expensive! They go for $34.95 (4 easy payments!) and up, easily. In addition, they are not easy to use—the user interfaces are counterintuitive, and there are somehow both too many options and not enough when it comes to searching. It would be nice if there were something in the middle.

In steps Google Scholar. It might feel like using Wikipedia—I mean, it looks real helpful, but that in itself means that you can’t use it, right? Well, kinda. So, as with Wikipedia, it’s really not good for some of the things that you might want to use it for, it’s kinda okay for some other things, and it’s downright more than kinda useful for some others. Here, we’ll talk a little bit about each so you have a clear sense for what it can and can’t do, why that is, and how to maximize the dissertation assistance or thesis help it can provide for you.

Not Regular-Google

Yep, definitely not that. It’s Google Scholar—scholar.google.com. Different address. It shows you not the worldwide web, but rather the worldwide web of academia, or something like that. First, it indexes articles in a variety of subject areas, and in this way, it acts a lot like a database, like ERIC for education, PSYCInfo, EBSCOHost, and a variety of others might work.

However, unlike at least ERIC and PSYCInfo, it pulls from sources in a variety of subjects. It’s pretty useful in this way, and it’s like an all-purpose database in its ability to provide sources in fields like Health and Medical Sciences, Social Sciences, Business, Economics and Management, and a variety of others (note that these are how Google Scholar itself categorizes the fields they provide sources). Just see their metrics—a peek inside can help us to see how much coverage they have in different fields. A quick scan shows us that there’s a good deal more they have in the “hard” sciences, including Chemical and Material Sciences, Engineering and Computer Science, and Health and Medical Science (this is the big one) than they do in the Social Sciences or in Humanities, Literature, and Arts (this is the little one).

The metrics linked to and described up there are organized by journal, and they have a lot of those—journal articles.

However, one of the cool things that they have is called “gray literature”, and this would consist of useful, non-journal sources like technical reports, working papers, committee reports, government documents, conference proceedings, and symposia. These can be super helpful, though a quick warning: Many of you are working with literature review guidelines that require you to use only peer-reviewed research. Gray literature, though produced by universities, research centers, and the like, are not peer-reviewed.

It does all this stuff while also offering a snazzy(-ish), Google-powered search experience. It looks familiar! That’s definitely a good thing.

How Not to Use Google Scholar

I think we know Google Scholar, by the way, pretty well now. Let’s just call it GS going forward. GS looks pretty good—it looks like Google—but just like that place, it’s really just a warehouse for stuff. It’s not curated by dissertation consultants, for example, so while some of it is primo stuff, some of it is garbage. There are lots of dangers, then, in simply relying on GS exclusively or uncritically.

First, GS is not a one-stop shop—this is the “exclusively” part. So the weird thing about it is that has so much stuff but, at the same time, not all of it. That does make a kind of sense, in that, in its attempt to grab a whole bunch of articles and other sources, things (and sometimes really useful things) slip between its fingers. Indeed, in a study by Haddaway, Collins, Coughlin, and Kirk (2015), it was compared against the Web of Science as a tool for the conduct of literature reviews. While researchers found that most literature yielded in a Web of Science search did also appear in GS, there was only poor or moderate overlap in results generated from search strings, with GS overlooking an important many sources in five of the six case studies the researchers conducted. Particularly when your literature reviewmust contain at least 75 sources and be at least 40 pages in length, each source counts, and the exclusive reliance on GS can leave you without all that you need.

The other problem is that it’s not always easy to find everything that is there. The aforementioned study found that the majority of gray literature was found at page 80 in a set of search results—most people don’t go past page 1! You might not be looking for gray literature, but still, the lack of Boolean and truncated search options means that you’ll have to take on multiple, tedious searches when you want to try different forms of search terms. This takes a task that would involve a single, streamlined iteration and turns it into one with several, with results overlapping and leaving you wondering when you’ve found everything.

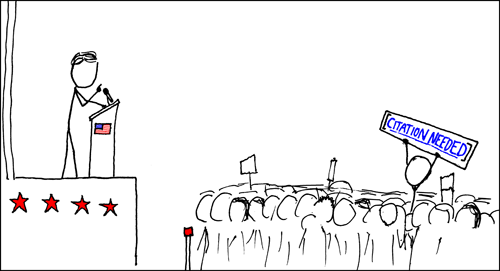

Now for the “uncritical” part. I alluded to this above, but with its grabby hands, GS also pulls in a lot of the riff raff. Again, given your likely need to rely fully on peer-reviewed research, this is important: There is no way to restrict your results to peer-reviewed studies. This means the additional work of finding a useful source and then hunting down that journal independently to find if it’s peer-reviewed.

“Well, I mean, how many journals could there be that aren’t peer-reviewed?” A bunch. A bunch of journals aren’t peer-reviewed. Some are well-intentioned, I should say, but some are actually predatory journals. Yep, these are a thing. See, there is something called open-access publishing, where users don’t actually have to pay $34.95 or more, regardless of the number of payments, to get to a source—instead, they can find it in its full-text glory at no charge.

The cost does go somewhere, though, and it’s goes straight to unsuspecting researchers. You know, people who have just finished their dissertations and want to pursue publication (now you know to watch out for these later on—and we can help you navigate the process!). An average payment an author might make to publish in a journal like this is $1,800, and predatory journals are happy to have this by pretending to be legitimate. There is no peer-review process, however, and what gets published is of, well, questionable quality.

These end up in GS along with the good stuff, so be careful—if it is riddled with typos, generally poorly-written, uses shoddy methods, or all of the above, check out the rest of what the journal has published. It might not be good.

Not Half-Bad

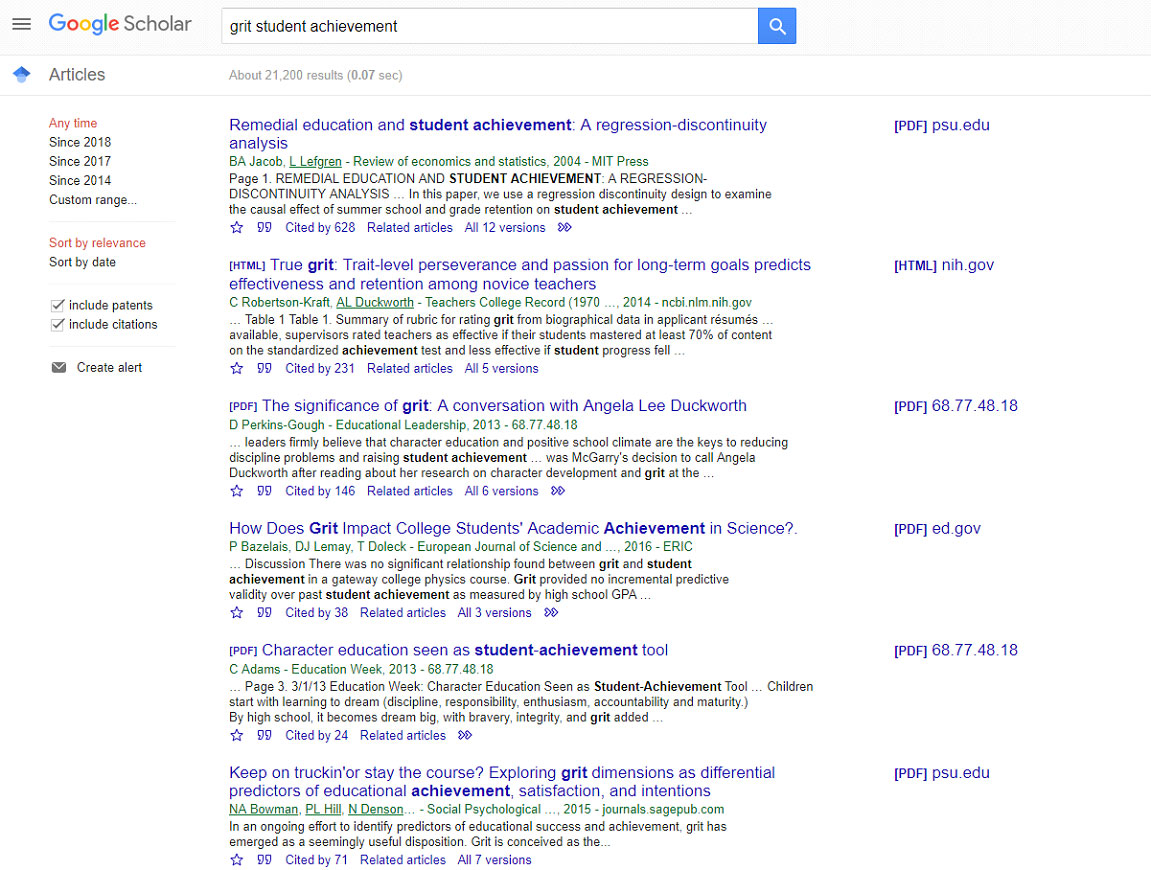

Okay okay, so those things are scary and not-good. However, GS grabs many good things when it fishes around for studies. And like I said before, it comes in a snazzy-ish package—one that is definitely more user-friendly than some databases. Here’s a set of results for a search:

Again, it’s pretty straightforward, though there are a few features that it is worth mentioning, simply as they’re really helpful ones:

- Date ranges. All of you have the burden in your dissertation or thesis writing of addressing current understandings in your respective fields. Some of you, though, even have downright crazy source recency requirements, such as that at least 85% of all sources be published within the last five years…from the date of defense. That means four years, really, if you’re just starting or doing your literature review. You can choose both from the pre-set list of range options and from the custom range option here in GS.

-

The “Cited by” feature. This is super cool. It allows you to see what other sources (on GS, remember) have cited the source in question. This can be really good for helping you to dive deeper into a line of inquiry. The deeper you go, the less focused it is, of course, but it’s a great way to find usually several more sources that are germane in some way to your research. It helps with the source recency issue, too, as the laws of time demand it (any source citing a source you found must necessarily have been published after that source).

- Full-text. These links off to the right take the user to a full-text version of the source in question. I should mention that other databases allow users to search only for full-text options, as well—GS just delivers this a little bit differently than do other search options.

- Custom alert. This option hangs out down there on the left by the date range selector, and it’s great for helping you keep up to date with anything that gets published as you’re doing your research or on things that have already been published but just get indexed by GS. The results get delivered to you, so you get to scroll through nice, manageable lists of new sources, picking and saving the ones that are relevant to your research. Some of you have the requirement to keep finding new sources and updating your literature review right up until final defense, and this feature—depending on how good your keyword-picking skills are—is a great asset to have.

-

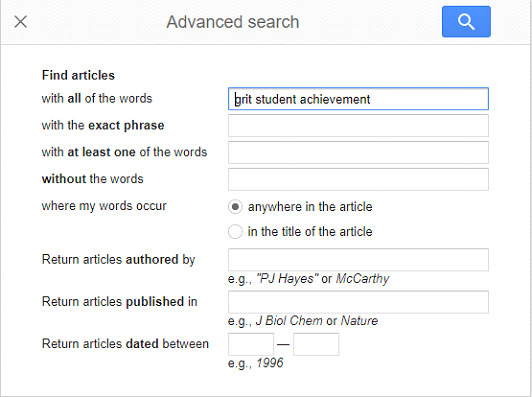

Advanced search. This is maybe the most useful tool for getting past keyword searches, and that is a really important thing to do, as any dissertation coach will tell you—remember that keyword searching, because of the lack of Boolean and truncated searching, is much more tedious and iterative in GS than in most scholarly databases. Advanced search offers a number of additional options beyond what the regular GS search offers:

Here, you can see that you get options to restrict your results to sources that show all the words you’ve entered, all the words exactly as you enter them, at least one of what might be several, and even without the words. Just as an example, I gave the example earlier of searching for ESSA, and this is the Every Student Succeeds Act. It replaced NCLB in December 2015, and maybe you got a comment about the need to talk about ESSA instead of NCLB. You might actually include NCLB or “No Child Left Behind” as an exclusionary term in this way, to get sources that talk about ESSA on its own terms.

Advanced search offers options, too, to search within the text of an article or stick with titles. In short, it has a lot, and the most robust features might be the author- and source-specific search options below.

Benefits Heretofore Unmentioned

While lots of benefits of GS are immediately apparent from the search features I mentioned above, many are not. Here are just some of them that are useful both overall and in specific research circumstances:

-

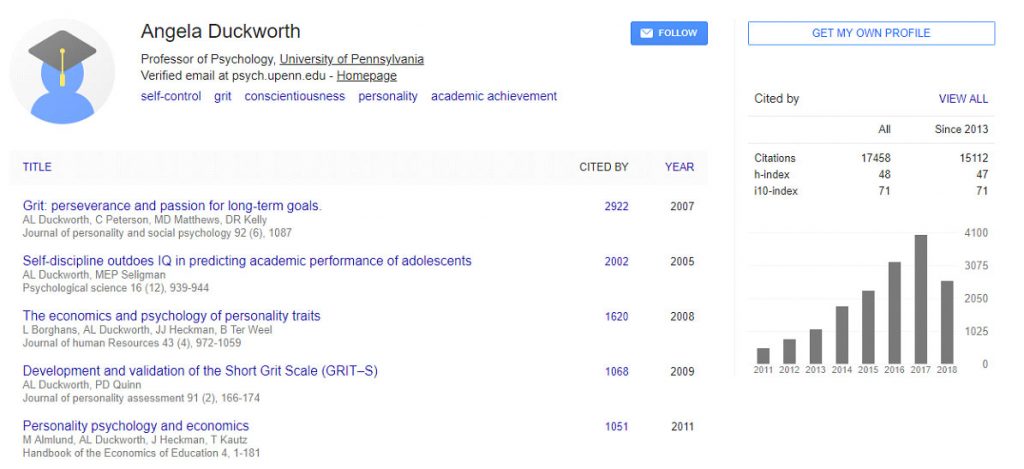

Author search. This was one of those options provided above in the advanced search bar. In the dissertation consulting we provide, we both recommend specific authors and find that our clients’ reviewers have done the very same. These are often authors of seminal work within the field or on the topic, and in some cases, the authors are the very reason there is a field in the first place. You can find articles by those authors by using that advanced search, and you can also do so by doing a GS search for a particular author. If they have a profile, then you can find out a lot about them. Here’s one for Angela Duckworth, who is responsible for transformative research on the concept of grit:

As you can see, she is pretty popular, and when you search for a researcher like her, you get citation frequencies, a list of the work she’s published (again, what available on GS), keywords most commonly associated with her, and even contact information. It’s quite robust, and it’s really helpful.

- “Digital snowball.” This is the term used by Zientek, Werner, Campuzano, and Nimon (2018) in their free-access article on GS (para. 10). Here, they say that the combined effect of the “cited by” feature (discussed above) and a quirk of GS that creates a list of publications that can provide either the most recent or most relevant results first is to guide researchers through a path of study on a particular topic. This is really helpful for seeing how inquiry on a question or set of questions has unfolded, and it’s something we get asked about a lot in our dissertation consulting work. I can’t say strongly enough how critically important this is when finding a research gap (for those of you finalizing your prospectus or concept paper)—your job is to position your study as the next logical step in the line of inquiry, and being able to trace it leading up to your research gap pays dividends for your problem statement, background section, and literature review all at the same time.

- Library links. This setting—it’s in the settings menu—allows you to select up to five libraries, allowing you to see the library access links for those libraries. This is particularly helpful because of the superior access to data you normally have as a university student—you get a free pass to so many sources that people without such access would have to pay for (again, given the cost, likely in installments, with the article on layaway). By establishing the library link, and likely logging into your university account or doing this from the campus or whatever might be needed (it varies per school), you can access many more full-text and other kinds of sources that are part of the university’s access.

Let’s Wrap This Up! We Got Searching to Do.

This is true! I can’t help but remind you of the caveats here—Google Scholar is really cool, but it is also a dangerous, non-one-stop shop for your research needs. There are articles from predatory journals here, and there are also definite gaps in their offerings, despite the fact that the number of results from any one search is bound to be huge.

If you keep those in mind and use Google Scholar as a supplement to other options, particularly those robust and peer-reviewed-source-only databases you have access to, then you should be well on your way to all the sources you need and a complete map of the field of study that you’re living on when you do your dissertation. Again, features like author search, the digital snowball, the “cited by” option, date ranges, and full-text-only searching mean that you have a fair amount of control over the sprawl.

And really, the whole point of this was to save you from those late-night searches. There is now definitely no need to use regular-Google to take on your desperate dissertation searching. Plus, there is a much easier way to find out how tall you are: First, take what you think is the right answer, add six inches, and then go out to the street. Call out for a person who is that height to come stand back to back with you. Be sure to get a third person—an any-heighted person—to be your viewer, and see if you are the same height as that person, shorter, or taller. If shorter or taller, select a height one inch in that direction, repeating the steps above until you reach a person who is the same height. You might want two any-heighted people to verify, just to be sure.

You’re welcome!

References

- Beall, J. (2012). Predatory publishers are corrupting open access. Nature, 489(179). doi:10.1038/489179a

- California State University, Long Beach. (2018). Gray literature. Retrieved from https://csulb.libguides.com/graylit

- Google Scholar. (2018). Top publications. Retrieved from https://scholar.google.com/citations?view_op=top_venues&hl=en&vq=phy

- Haddaway, N. R., Collins, A. M., Coughlin, D., & Kirk, S. (2015). The role of Google Scholar in evidence reviews and its applicability to grey literature searching. PLoS One, 10(9), e0138237. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0138237

- Zientek, L. R., Werner, J. M., Campuzano, M. V., & Nimon, K. (2018). The use of Google Scholar for research and research dissemination. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resources Development, 30(1). doi:10.1002/nha3.20209